Image 1 of 14

Image 1 of 14

Image 2 of 14

Image 2 of 14

Image 3 of 14

Image 3 of 14

Image 4 of 14

Image 4 of 14

Image 5 of 14

Image 5 of 14

Image 6 of 14

Image 6 of 14

Image 7 of 14

Image 7 of 14

Image 8 of 14

Image 8 of 14

Image 9 of 14

Image 9 of 14

Image 10 of 14

Image 10 of 14

Image 11 of 14

Image 11 of 14

Image 12 of 14

Image 12 of 14

Image 13 of 14

Image 13 of 14

Image 14 of 14

Image 14 of 14

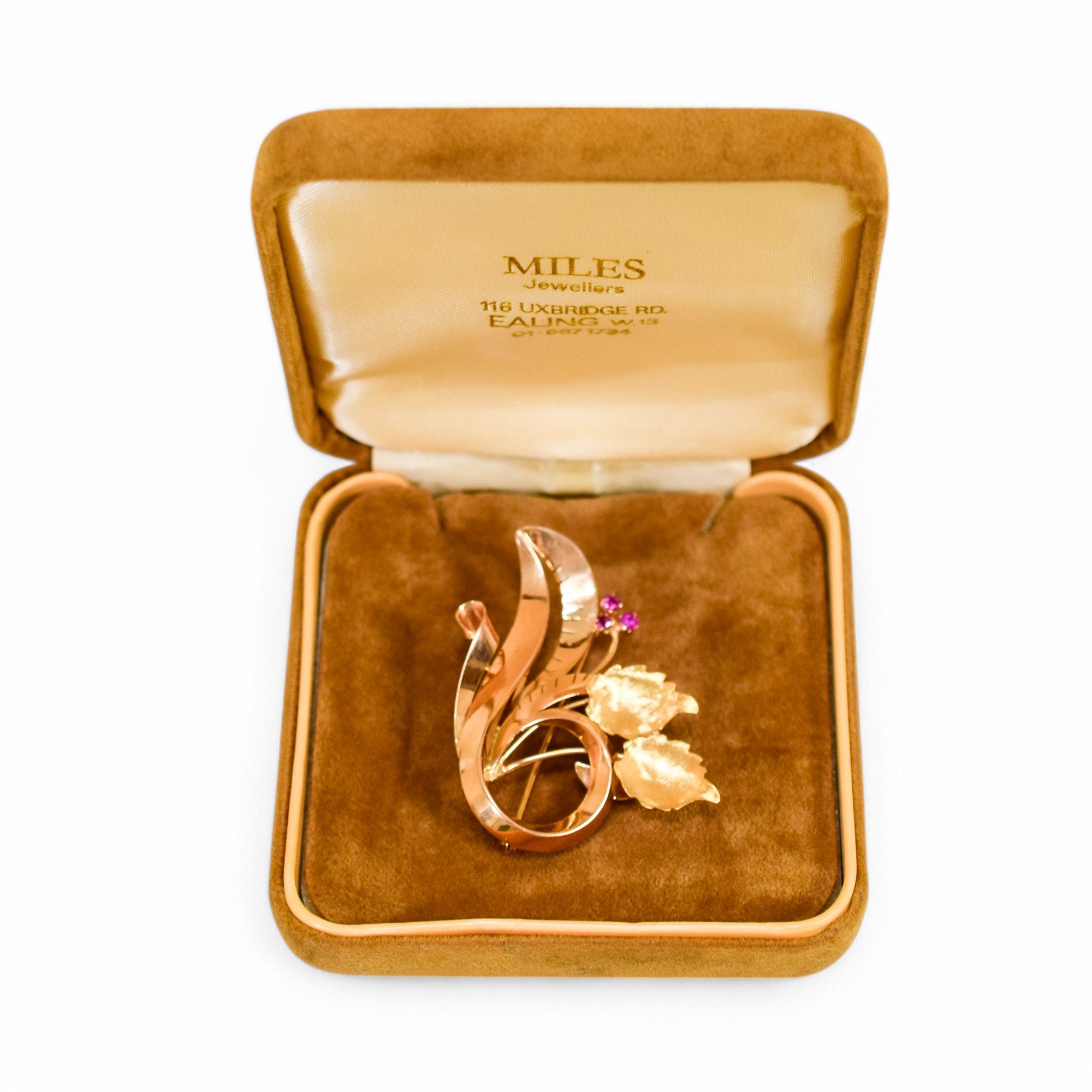

1820’s Georgian pinchbeck gold torpedo chandelier pendant decorated with cannetille and filigree

Early 19th century Georgian pinchbeck gold earring fashioned into a pendant with a 20th century necklace and bale. Typical Georgian torpedo form with an openwork body that is decorated with embossed scrolls and leaves on one side and cannetille flowers on the other.

Made in England, c. 1820’s.

Necklace – 44.5 cm

Pendant - 6.2 cm long, 2 cm across widest part

Soldering just above the large filigree flower and to base of pendant. Several small holes, one side slightly pushed in.

Early 19th century Georgian pinchbeck gold earring fashioned into a pendant with a 20th century necklace and bale. Typical Georgian torpedo form with an openwork body that is decorated with embossed scrolls and leaves on one side and cannetille flowers on the other.

Made in England, c. 1820’s.

Necklace – 44.5 cm

Pendant - 6.2 cm long, 2 cm across widest part

Soldering just above the large filigree flower and to base of pendant. Several small holes, one side slightly pushed in.

In the early 1700s a renowned clockmaker named Christopher Pinchbeck created an alloy of zinc and copper which bore a remarkable similarity to gold, and came to bear his name. Pinchbeck was not intending to deceive people into mistaking it for gold, but to act as a substitute for those not able to afford 18ct gold, as this was the only gold alloy available at the time, until the law changed in 1854 and lower purity of gold was allowed to be made

The lower value of pinchbeck jewellery also meant that it was safer to wear it when travelling. Unfortunately during the years following the development of the first pinchbeck many unscrupulous individuals did try to pass it off as gold, which led to the material being viewed as inherently duplicitous. Today genuine pinchbeck jewellery is highly valued and collectible in its own right, particularly pieces which come from the material’s early use in the Georgian period.